According to accepted ideas of ocular hygiene, it is important to protect the eyes from a great variety of influences which are often very difficult to avoid, and to which most people resign themselves with the uneasy sense that they are thereby “ruining their eyesight.” Bright lights, artificial lights, dim lights, sudden fluctuations of light, fine print, reading in moving vehicles, reading lying down, etc., have long been considered “bad for the eyes,” and libraries of literature have been produced about their supposedly direful effects. These ideas are diametrically opposed to the truth. When the eyes are properly used, vision under adverse conditions not only does not injure them, but is an actual benefit, because a greater degree of relaxation is required to see under such conditions than under more favorable ones. It is true that the conditions in question may at first cause discomfort, even to persons with normal vision; but a careful study of the facts has demonstrated that only persons with imperfect sight suffer seriously from them, and that such persons, if they practice central fixation, quickly become accustomed to them and derive great benefit from them.

Although the eyes were made to react to the light, a very general fear of the effect of this element upon the organs of vision is entertained both by the medical profession and by the laity. Extraordinary precautions are taken in our homes, offices and schools to temper the light, whether natural or artificial, and to insure that it shall not shine directly into the eyes; smoked and amber glasses, eye-shades, broad-brimmed hats and parasols are commonly used to protect the organs of vision from what is considered an excess of light; and when actual disease is present, it is no uncommon thing for patients to be kept for weeks, months and years in dark rooms, or with bandages over their eyes.

The evidence on which this universal fear of the light has been based is of the slightest. In the voluminous literature of the subject one finds such a lack of information that in 1910 Dr J. Herbert Parsons of the Royal Ophthalmic Hospital of London, addressing a meeting of the Ophthalmological Section of the American Medical Association, felt justified in saying that ophthalmologists, if they were honest with themselves, “must confess to a lamentable ignorance of the conditions which render bright light deleterious to the eyes.”(1) Since then, Verhoeff and Bell have reported(2) an exhaustive series of experiments carried on at the Pathological Laboratory of the Massachusetts Charitable Eye and Ear Infirmary, which indicate that the danger of injury to the eye from light radiation as such has been “very greatly exaggerated.” That brilliant sources of light sometimes produce unpleasant temporary symptoms cannot, of course, be denied; but as regards definite pathological effects, or permanent impairment of vision from exposure to light alone, Drs. Verhoeff and Bell were unable to find, either clinically or experimentally, anything of a positive nature.

As for danger from the heat effects of light, they consider this to be “ruled out of consideration by the immediate discomfort produced by excessive heat.” They conclude, in short, that “the eye in the process of evolution has acquired the ability to take care of itself under extreme conditions of illumination to a degree hitherto deemed highly improbable.” In their experiments, the eyes of rabbits, monkeys and human beings were flooded for an hour or more with light of extreme intensity, without any sign of permanent injury, the resulting scotomata(3) disappearing within a few hours. Commercial illuminants were found to be entirely free of danger under any ordinary conditions of their use. It was even found impossible to damage the retina with any artificial illuminant, except by exposures and intensities enormously greater than any likely to occur outside the laboratory. In one case an animal succumbed to heat after an exposure of an hour and a half to a 750-watt nitrogen lamp at twenty centimeters-about eight inches; but in a second experiment, in which it was well protected from the heat, there was no damage to the eye whatever after an exposure of two hours. As for the ultra violet part of the spectrum, to which exaggerated importance has been attached by many recent writers, the situation was found to be much the same as with respect to the rest of the spectrum; that is, “while under conceivable or realizable conditions of overexposure injury may be done to the external eye, yet under all practicable conditions found in actual use of artificial sources of light for illumination the ultra violet part of the spectrum may be left out as a possible source of injury.”

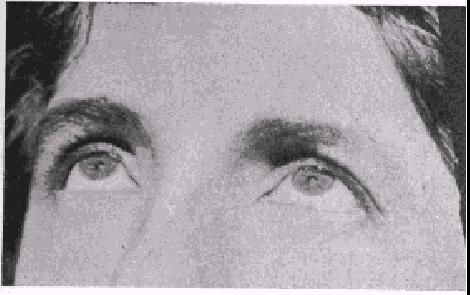

Fig. 46. Woman With Normal Vision Looking Directly at the Sun. Note That the Eyes are Wide Open and That There Is No Sign of Discomfort.

The results of these experiments are in complete accord with my own observations as to the effect of strong light upon the eyes. In my experience such light has never been permanently injurious. Persons with normal sight have been able to look at the sun for an indefinite length of time, even an hour or longer, without any discomfort or loss of vision. Immediately afterward they were able to read the Snellen test card with improved vision, their sight having become better than what is ordinarily considered normal. Some persons with normal sight do suffer discomfort and loss of vision when they look at the sun; but in such cases the retinoscope always indicates an error of refraction, showing that this condition is due, not to the light, but to strain. In exceptional cases persons with defective sight have been able to look at the sun, or have thought that they have looked at it, without discomfort and without loss of vision; but, as a rule, the strain in such eyes is enormously increased and the vision decidedly lowered by sungazing, as manifested by inability to read the Snellen test card. Blind areas (scotomata) may develop in various parts of the field-two or three or more. The sun, instead of appearing perfectly white, may appear to be slate-colored, yellow, red, blue, or even totally black. After looking away from the sun, patches of color of various kinds and sizes may be seen, continuing a variable length of time, from a few seconds to a few minutes, hours, or even months. In fact, one patient was troubled in this way for a year or more after looking at the sun for a few seconds. Even total blindness lasting a few hours has been produced. Organic changes may also be produced. Inflammation, redness of the conjunctiva, cloudiness of the lens and of the aqueous and vitreous humors, congestion and cloudiness of the retina, optic nerve and choroid, have all resulted from sun-gazing. These effects, however, are always temporary. The scotomata, the strange colors, even the total blindness, as explained in the preceding chapter, are only mental illusions. No matter how much the sight may have been impaired by sun-gazing, or how long the impairment may have lasted. a return to normal has always occurred; while prompt relief of all the symptoms mentioned has always followed the relief of eyestrain, showing that the conditions are the result, not of the light, but of the strain. Some persons who have believed their eyes to have been permanently injured by the sun have been promptly cured by central fixation, indicating that their blindness had been simply functional.

By persistence in looking at the sun, a person with normal sight soon becomes able to do so without any loss of vision; but persons with imperfect sight usually find it impossible to accustom themselves to such a strong light until their vision has been improved by other means. On has to be very careful in recommending sun-gazing to persons with imperfect sight; because although no permanent harm can result from it, great temporary discomfort may be produced, with no permanent benefit. In some rare cases, however, complete cures have been effected by this means alone.

In one of these cases the sensitiveness of the patient, even to ordinary daylight, was 60 great that an eminent specialist had felt justified in putting a black bandage over one eye and covering the other with a smoked glass so dark as to be nearly opaque. She was kept in this condition of almost total blindness for two years without any improvement. Other treatment extending over some months also failed to produce satisfactory results. She was then advised to look directly at the sun. The immediate result was total blindness, which lasted several hours; but next day the vision was not only restored to its former condition, but was improved. The sungazing was repeated, and each time the blindness lasted for a shorter period. At the end of a week the patient was able to look directly at the sun without discomfort, and her vision, which had been 20/200 without glasses and 20/70 with them, had improved to 20/10, twice the accepted standard for normal vision.

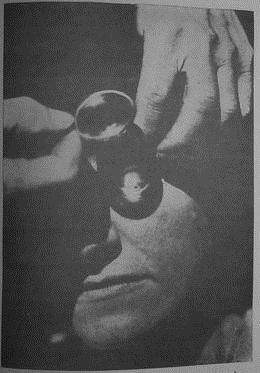

Patients of this class have also been greatly benefited by focussing the rays of the sun directly upon their eyes, marked relief being often obtained in a few minutes.

Fig. 47. Woman Aged 37, Child Aged 4, Both Looking

Directly at Sun Without Discomfort.

Like the sun, a strong electric light may also lower the vision temporarily, but never does any permanent harm. In those exceptional cases in which the patient can become accustomed to the light, it is beneficial. After looking at a strong electric light some patients have been able to read the Snellen test card better.

It is not light but darkness that is dangerous to the eye. Prolonged exclusion from the light always lowers the vision, and may produce serious inflammatory conditions. Among young children living in tenements this is a somewhat frequent cause of ulcers upon the cornea, which ultimately destroy the sight. The children, finding their eyes sensitive to light, bury them in the pillows and thus shut out the light entirely. The universal fear of reading or doing fine work in a dim light is, however, unfounded. So long as the light is sufficient so that one can see without discomfort, this practice is not only harmless, but may be beneficial.

Sudden contrasts of light are supposed to be particularly harmful to the eye. The theory on which this idea is based is summed up as follows by Fletcher B. Dresslar, specialist in school hygiene and sanitation of the United States Bureau of Education:

“The muscles of the iris are automatic in their movements, but rather slow. Sudden contrasts of strong light and weak illumination are painful and likewise harmful to the retina. For example, if the eye, adjusted to a dim light, is suddenly turned toward a brilliantly lighted object, the retina will receive too much light and will be shocked before the muscles controlling the iris can react to shut out the superabundance of light. If contrasts are not strong, but frequently made, that is, if the eye is called upon to function where frequent adjustments in this way are necessary, the muscles controlling the iris become fatigued, respond more slowly and less perfectly. As a result, eyestrain in the ciliary muscles is produced and the retina is over-stimulated. This is one cause of headaches and tired eyes.”(4)

Fig. 48. Focussing the Rays of the Sun Upon the Eye of a

Patient by Means of a Burning Glass.

There is no evidence whatever to support these statements. Sudden fluctuations of light undoubtedly cause discomfort to many persons, but, far from being injurious, I have found them, in all cases observed, to be actually beneficial. The pupil of the normal eye, when it has normal sight, does not change appreciably under the influence of changes of illumination; and persons with normal vision are not inconvenienced by such changes. I have seen a patient look directly at the sun after coming from an imperfectly lighted room, and then, returning to the room, immediately pick up a newspaper and read it. When the eye has imperfect sight, the pupil usually contracts in the light and expands in the dark, but it has been observed to contract to the size of a pinhole in the dark. Whether the contraction takes place under the influence of light or of darkness, the cause is the same, namely, strain. Persons with imperfect sight suffer great inconvenience, resulting in lowered vision, from changes in the intensity of the light; but the lowered vision is always temporary, and if the eye is persistently exposed to these conditions, the sight is benefited. Such practices as reading alternately in a bright and a dim light, or going from a dark room to a well-lighted one, and vice versa, are to be recommended. Even such rapid and violent fluctuations of light as those involved in the production of the moving picture are, in the long run, beneficial to all eyes. I always advise patients under treatment for the cure of defective vision to go to the movies frequently and practice central fixation. They soon become accustomed to the flickering light, and afterward other light and reflections cause less annoyance.

Reading is supposed to be one of the necessary evils of civilization; but it is believed that by avoiding fine print, and taking care to read only under certain favorable conditions, its deleterious influences can be minimized. Extensive investigations as to the effect of various styles of print on the eyesight of school children have been made, and detailed rules have been laid down as to the size of the print, its shading, the distance of the letters from each other, the spaces between the lines, the length of the lines, etc.. As regards the effects of different sorts of type on the human eye in general and those of children in particular, Dr. A. G. Young, in his much quoted report(5) to the Maine State Board of Health makes the following interesting observations:

Pearl. as the printers call it, is unfit for any eves, yet the piles of Bibles and Testaments annually printed in it tempt many eyes to self-destruction.

Agate is the type in which a boy, to the writer’s knowledge, undertook to read

the Bible through, His outraged eyes broke down with asthenopia before he went

far and could be used but little for school work the next two years.

Nonpareil is used in some papers and magazines for children, but, to spare the eyes, all such should, and do, go on the list of forbidden reading matter in those homes where the danger of such print is understood.

Minion is read by the healthy, normal young eye without appreciable difficulty, but even to the sound eye the danger of strain is so great that all books and magazines for children printed from it should be banished from the home and school.

Brevier is much used in newspapers, but is too small for magazines or books for young folks.

Bourgeois is much used in magazines, but should he used in only those school books to which a brief reference is made.

Long Primer is suitable for school readers for the higher and intermediate grades, and for text books generally.

Small Pica is still a more luxurious type, used in the North American Review and the Forum.

Pica is a good type for books for small children.

Great Primer should be used for the first reading book.

[Note: The text above is not sized larger and smaller as it is in the original book. – DK]

All this is directly contrary to my own experience. Children might be bored by books in excessively small print; but I have never seen any reason for supposing that their eyes, or any other eyes, would be harmed by such type. On the contrary, the reading of fine print, when it can be done without discomfort, has invariably proven to be beneficial, and the dimmer the light in which it can be read, and the closer to the eyes it can be held, the greater the benefit. By this means severe pain in the eyes has been relieved in a few minutes or even instantly. The reason is that fine print cannot be read in a dim light and close to the eyes unless the eyes are relaxed, whereas large print can be read in a good light and at ordinary reading distance although the eyes may be under a strain. When fine print can be read under adverse conditions, the reading of ordinary print under ordinary conditions is vastly improved. In myopia it may be a benefit to strain to see fine print, because myopia is always lessened when there is a strain to see near objects, and this has sometimes counteracted the tendency to strain in looking at distant objects, which is always associated with the production of myopia. Even straining to see print so fine that it cannot be read is a benefit to some myopes.

1–Normal Sight can always be demonstrated in the normal eye, but only under favorable conditions.

>2–Central Fixation: The letter or part of the letter regarded is always seen best.

3–Shifting: The point regarded changes rapidly and continuously.

4–Swinging: When the shifting is slow, the letters appear to move from side to side or in other directions with a pendulum-like motion.

5–Memory is perfect The color and background of the letters, or other objects seen are remembered perfectly, instantaneously and continuously.

6–Imagination is good. One may even see the white part of the letters whiter than it really is, while the black is not altered by distance, illumination, size, or form, of the letters.

7–Rest or relaxation of the eye and mind is perfect and can always be demonstrated.

When one of these seven fundamentals is perfect all are perfect.

Many patients have been greatly benefited by reading type of this size.

[Note: Although the sample from Bates’s book is diamond type, the text above is not. – DK]

Persons who wish to preserve their eyesight are frequently warned not to read in moving vehicles; but since under modern conditions of life many persons have to spend a large part of their time in moving vehicles, and many of them have no other time to read, it is useless to expect that they will ever discontinue the practice. Fortunately the theory of its injuriousness is not borne out by the facts. When the object regarded is moved more or less rapidly, strain and lowered vision are, at first, always produced; but this is always temporary, and ultimately the vision is improved by the practice.

There is probably no visual habit against which we have been more persistently warned than that of reading in a recumbent posture. Many plausible reasons have been adduced for its supposed injuriousness; but so delightful is the practice that few, probably, have ever been deterred from it by fear of the consequences. It is gratifying to be able to state, therefore, that I have found these consequences to be beneficial rather than injurious. As in the case of the use of the eyes under other difficult conditions, it is a good thing to be able to read lying down, and the ability to do it improves with practice. In an upright position, with a good light coming over the left shoulder, one can read with the eyes under a considerable degree of strain; but in a recumbent posture, with the light and the angle of the page to the eye unfavorable, one cannot read unless one relaxes. Anyone who can read lying down without discomfort is not likely to have any difficulty in reading under ordinary conditions.

The fact is that vision under difficult conditions is good mental training. The mind may be disturbed at first by the unfavorable environment; but after it has become accustomed to such environments, the mental control, and, consequently, the eyesight are improved. To advise against using the eyes under unfavorable conditions is like telling a person who has been in bed for a few weeks and finds it difficult to walk to refrain from such exercise. Of course, discretion must be used in both cases. The convalescent must not at once try to run a Marathon, nor must the person with defective vision attempt, without some preparation, to outstare the sun at noonday. But just as the invalid may gradually increase his strength until the Marathon has no terrors for him, so may the eye with defective sight be educated until all the rules with which we have so long allowed ourselves to be harassed in the name of “eye hygiene” may be disregarded, not only with safety but with benefit.

Patients who can read photographic type reductions are instantly relieved of pain and discomfort when they do so and those who cannot read such type may be benefited simply by looking at it.

[Note: Although the sample from Bates’s book is clear enough to be readable, the scanned picture above is of too low quality to be readable. – DK]

1. Jour. Am. Med. Assn., Dec. 10, 1910, p. 2028.

2. Proc. Am. Acad. Arts and Sciences, 1916, Vol. 51, No. 13.

3. Blind areas.

4. School Hygiene, Brief Course Series in Education, edited by Monroe, 1916, p. 240.

5. Seventh Annual Report to the Maine State Board of Health, by the secretary, Dr. A. G. Young, 1891, p. 193.